Gait Laboratory Testing

Information-led design and manufacturing

At 3D Printed Orthotics we do not believe there is a single best orthotic for all your patients and their pathologies. We do not claim we have an orthotic which alone will ‘cure your plantar fasciitis’, ‘realign your foot’ or ‘give you your arch back’. Unfortunately, these are marketing claims made by unscrupulous sellers.

Although we do not have all the answers around how orthotics work, what we do know is that they are consistently shown to provide symptomatic relief for patients. The current prevailing theory is that orthotics alter the load in tissues (kinetics), even when there are no visible angular change at joints (kinematics). Combining this with paradigms like The Tissue Stress Theory (Kirby 2002/13), The Envelope of Function (Dye 1996) and Zones of Optimal Stress (Spooner) provides a framework for how orthotics provide a therapeutic effect.

Why Use a Gait Laboratory

Traditional gait analysis has typically been done using technologies such as force plates, short pressure platforms and motion capture video. These are limited as they capture static data, a very small number of steps and/or kinematic changes. This leads to problems of static vs dynamic gait, double limb support vs single limb, conscious or unconscious gait alterations to hit the force platform, variability between foot strikes, real world walking vs laboratory conditions, kinematics poor prediction of pathology, etc.

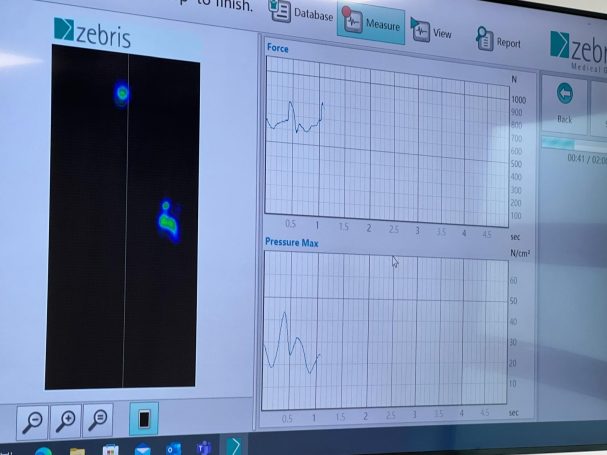

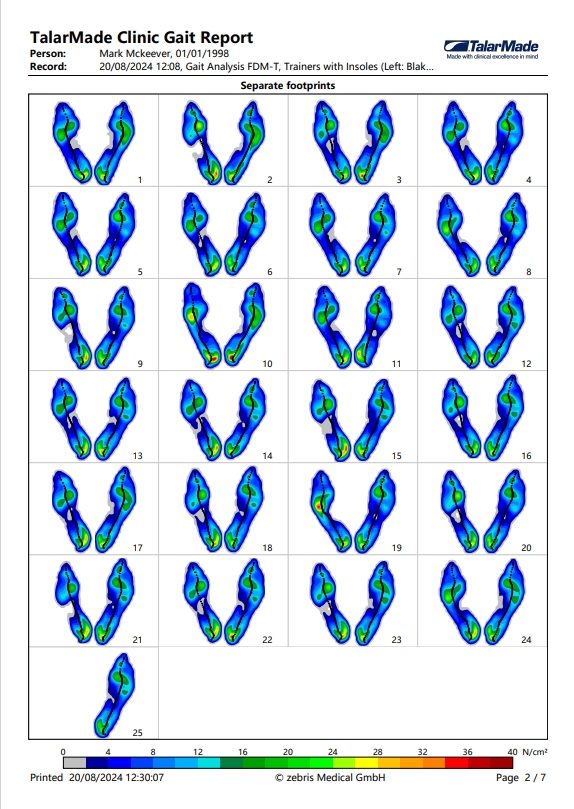

We have tested our orthotics in a gait laboratory using the most up to date Zebris dynamic gait analysis. The Zebris pressure distribution treadmill allows for the observation of the human gait at different speeds and inclinations over a high number of step repetitions. Thousands of individually calibrated sensors and compensation for the movement of the treadmill enables exact measuring from heel strike to toe off.

Figure 1 – Multiple steps captured within one test. The variation between each foot strike can be seen even in this controlled environment.

The data generated from gait analysis of our orthotics helps us to improve our product quality and user experience as well as driving innovation and development and supporting continuous improvement.

Standing on the shoulders of previous researchers we have focused on two variables in biomechanics. These variables are the centre of pressure and loading rates. These two variables have been highlighted as being of crucial importance in pathomechanics. Developing a deeper understanding of how our orthotics can predictably manipulate these variables will give you the confidence to implement our orthotics with reliable results.

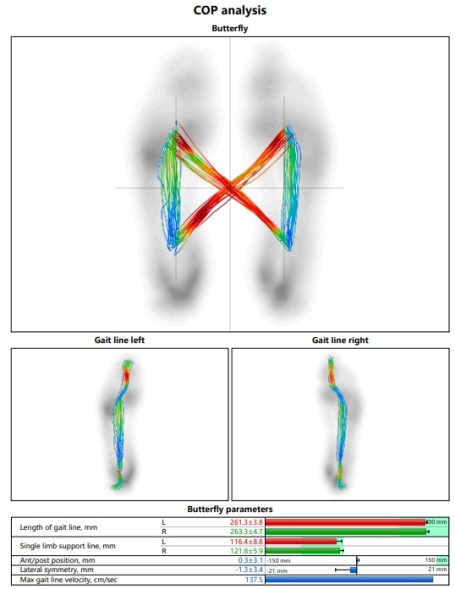

Figure 2 – Zebris dynamic gait analysis

Importance of Centre of Pressure

The Centre of Pressure (CoP) is the point at which the total Ground Reaction Force (GRF) (the equal and opposite response to the force an individual exerts on the ground) is acting on a person’s foot/feet. In gait analysis the CoP can be used to reflect the progression of the centre of mass during gait. CoP is crucial in maintaining stability and creating joint moments necessary for gait.

Tracking CoP during dynamic gait analysis provides a deeper understanding of displacement, velocity and acceleration occurring around joints. These variables have been suggested as contributing to injury.

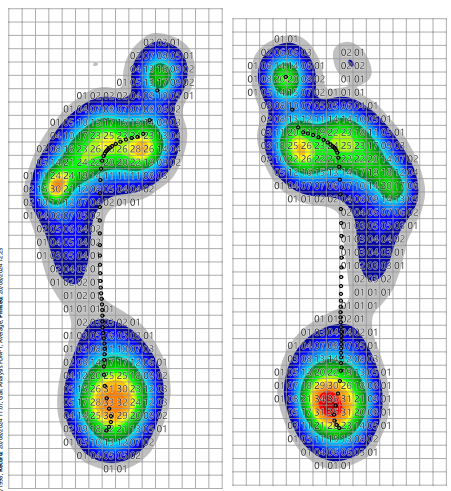

Figure 3 – Centre of pressure and force data

The geometry of an orthotic can manipulate the CoP and through this change the loading in targeted tissues. For example, increasing the medial GRF using things such as medial heel skives, medial posts and medial flanges, will create a larger supinatory moment and so reduce the load intrinsically in body tissues such as tibialis posterior, tibialis anterior, flexor hallucis longus, flexor hallucis brevis and the plantar fascia. Similarly, on an appropriate patient using a lateral forefoot wedge will move the CoP to the lateral forefoot by creating a high GRF under the lateral forefoot and so introduce a pronatory moment. This could be useful in treating peroneal tendinopathy and has indeed been shown to reduce peroneal longus activity in EMG studies.

The Importance of Rate of Loading

Loading rate is the speed at which forces act on the body and is calculated by dividing the maximum force by the time the body was exposed to this force. Simply put, the rate of loading is the speed at which you are applying force/s to the human body. It has been suggested that the rate of loading is one of the most important load variables in its relation to injury.

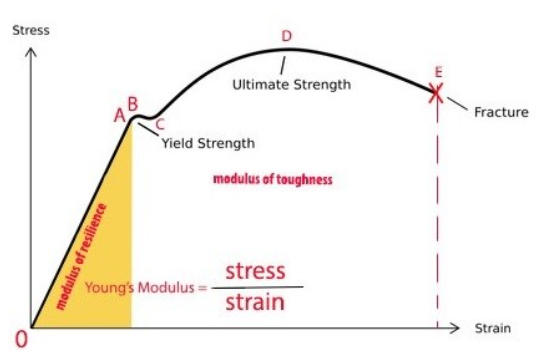

Due to their viscoelastic properties, all musculoskeletal tissue of the human body will behave differently when loaded at different rates. For example, ligaments typically fail under very high loading rates whereas bone will typically fail at lower loading rates with higher loading cycles. It is also worth mentioning that tissues will often have a preferred purpose (compression, flexion, torsion). Tissue loaded outside of their intended purpose will also increase the likelihood of injury. A tissue loaded outside of its intended purpose AND under high loading rates will exponentially increase injury risk. The ability of a tissue to handle load can be visually depicted with the stress-strain curve, this curve will alter in appearance depending on the speed at which load is applied.

Figure 4 – Stress-strain curve

An example of loading rates during gait would be at initial contact where the rapid deceleration and momentum change of the limb can reach up to three times bodyweight and generate a transient force that is transmitted along the musculoskeletal system. Rate of loading is influenced by GRF as well as the body having the ability to modulate and damped loading rates through muscle contraction and limb segment motion. With the above example it is easy to see how loading rates could be increased when moving from walking to running or more powerful movements, as muscle strength decreases with fatigue, with increasing bodyweight, etc. Reducing loading rates can be done through several ways, e.g., altering gait, changes in footwear and increasing muscle strength.

With foot orthoses we can control rate of loading through our understand and selection of material properties being used to reduce or alter GRF and to assist our intrinsic active and passive control tissues. For example, loading rates in the forefoot can be increased due to Achilles tendon limitations. Alongside an appropriate rehabilitation protocol, an orthotic could be used to cushion the forefoot (material properties) and raise the heel (through the shell geometry) to successfully lower forefoot loading rates.

Figure 5 – Change in loading rates and peak loading without orthotic (left) vs with orthotic intervention (right)

©Copyright. All rights reserved.

We need your consent to load the translations

We use a third-party service to translate the website content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details in the privacy policy and accept the service to view the translations.